A London based magazine History Today in its February, 2019 issue documents inter alia ABVA's role in the repeal of Section 377 IPC.

India Breaks Free?

India’s decision to decriminalise homosexuality is presented as the country shaking off the last vestiges of colonialism. The reality is not so simple.

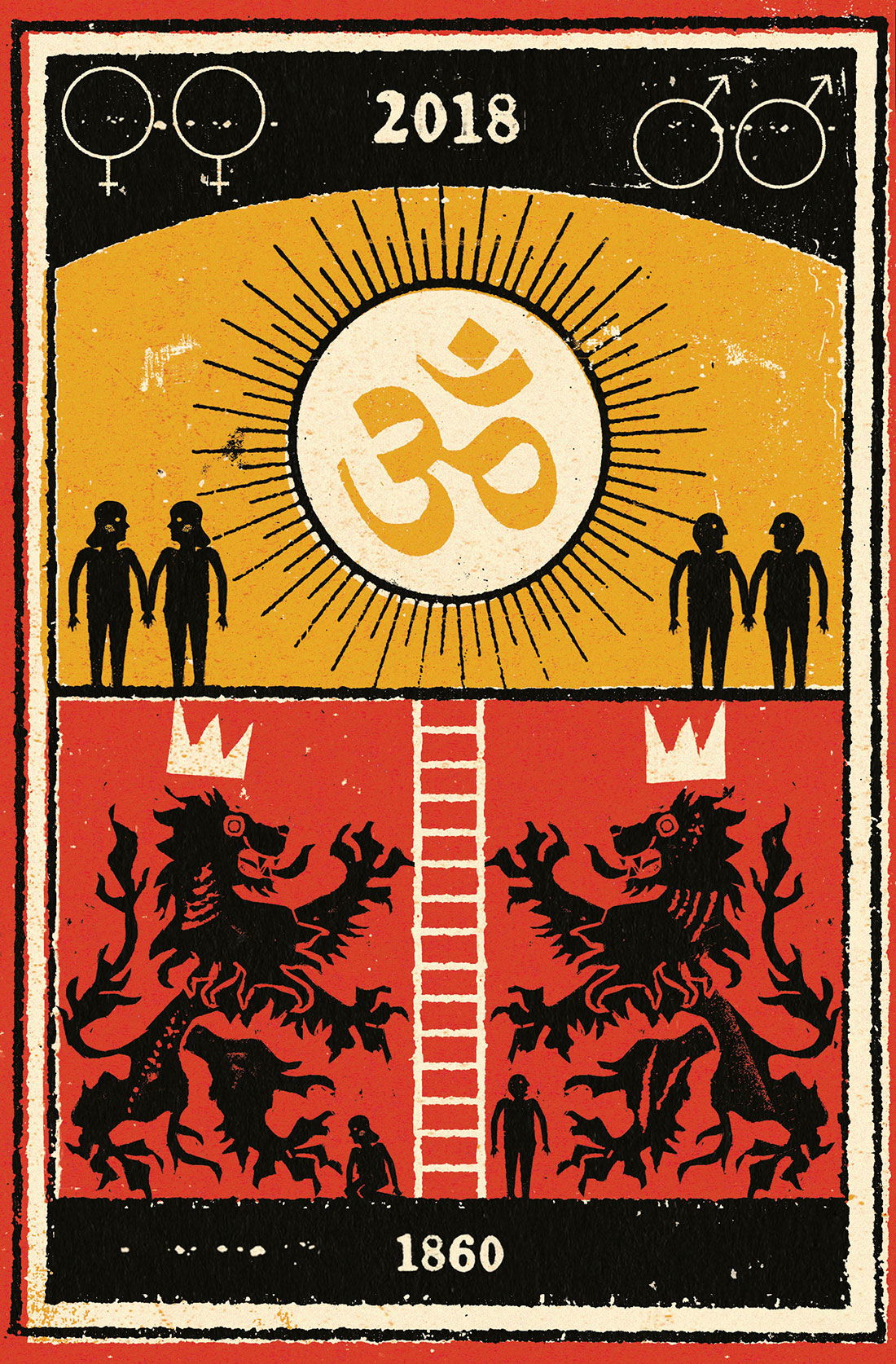

Illustration by Ben Jones.On 6 September 2018, India, the world’s largest democracy, finally decriminalised homosexuality. This historic judgment was passed after years of courtroom battles, long and arduous campaigns and protests, organised by millions of citizens, organisations and activists. The moment was widely celebrated.

Illustration by Ben Jones.On 6 September 2018, India, the world’s largest democracy, finally decriminalised homosexuality. This historic judgment was passed after years of courtroom battles, long and arduous campaigns and protests, organised by millions of citizens, organisations and activists. The moment was widely celebrated.

For the first time, Indian citizens who identify as part of the LGBT community ceased to be outlawed. Initial reactions in the media reflected the populist idea that India had finally managed to break free of the shackles of colonialism. Within the first Indian Penal Code (1860), which came into force in January 1862, was Section 377, on ‘Unnatural Offences’. Based on the English Buggery Act (1533), it stated: ‘Whoever has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or … for a term which may extend to ten years, and shall also be liable to fine.’

‘History owes an apology to those who have been persecuted and socially ostracised because of Section 377’, noted Indu Malhotra, one of the five judges delivering the verdict in September. The partial repeal (rape will, of course, continue to be an offence, as will carnal intercourse with children and bestiality) was, however, only obtained after a prolonged and arduous battle against prejudice, illiteracy and the indifference of Indian lawmakers of all parties. In the years since India’s independence, no policymakers have endeavoured to remove the law, despite the fact that it violated the fundamental right to equality, upheld by the Constitution, effected in January 1950: ‘The state shall not deny to any person equality before the law [on grounds] of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth ...’

Ancient precedents

It is easy to understand why the decriminalisation of homosexuality might be seen as a return to India’s pre-colonial values. There are countless references to homosexuality and third-gender (those who are neither ‘male’ or ‘female’, either biologically or in presentation) in ancient Indian texts and epics. The Sanskrit epic the Mahabharata includes the tale of Shikhandi, born female, who later becomes male, though a eunuch. In the Ramayana (which, with the Mahabharata, forms the Hindu Mahakavyas, ‘epics’), describes Hanuman witnessing women kissing and also King Bhagirath’s birth from the union of two women. Ancient medical texts, such as Charaka Samhita, explain the reasons for different sexual behaviours and genders. Perhaps the most familiar Hindu depiction of third-gender is embodied by Ardhanarishvara, the androgynous form of the male Shiva and female Parvati, split down the middle equally, in which form Shiva pursues Vishnu – who has taken the form of a female enchantress.

These ancient texts were written when the region now known as India was under the sacrificial religion Brahmanism, essentially created by the upper caste (the priests) in the Vedic and post-Vedic periods (c.1500-500 BC). Hinduism, derived from Brahmanism, generally accepted the third-gender as natural. From the 12th century onwards, Muslim conquests failed to impact the entire Indian subcontinent and many regions continued to follow their traditional beliefs. Homosexuality was not frowned upon among the ruling classes – Muslim rulers such as Alauddin Khalji allegedly had male harems – although it was not as common among the people.

Who’s to blame?

The law criminalising homosexuality found itself a place in the Indian Penal Code (IPC) under the pretext of protecting family values and morality. Even though instances of convictions for homosexuality have been rare – with perhaps only 120-170 cases in the last 150 years – as a result of the law, gay and lesbian people have had to live as second-class citizens, facing harassment and prejudice, as ‘unconvicted felons’. This attitude has systematically driven sexual minorities, especially transgender people, to the fringes of society. Post-independence, India, with its apparent secular but Hindu-aligned ideologies, has striven to accuse either its colonial past or former Muslim rulers of actively stigmatising homosexuality, transforming it into something ‘unnatural’. Despite this, there has been little desire to change these attitudes and negligible public dialogue on the subject. Gay people remained largely invisible in the eyes of both the law and government. Only in the late 20th century, with the establishment of several gay rights organisations, did homosexuality start to be widely discussed and debated. India began to acknowledge the existence of gays only after sexual health became a matter of concern for the Indian government in the late 1980s.

The Stonewall riots of 1969 mark the origin of the modern gay rights movement in the US. India witnessed its first such protest in 1991 with the publication of Less than Gay, which described itself as a ‘A citizens’ report on the status of homosexuality in India’. It was prepared by seven members of the group AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan (AIDS Anti-Discrimination Movement, or ABVA). The group began with 14 members, including doctors, lawyers and activists, who had been associated with social welfare activities in India for decades. They became the first organised group in India to work for people affected by HIV. They also started to work towards legalising homosexuality, filing a petition in 1994 challenging the legality of Section 377. The ABVA and its activities reached many people, bolstered by the Naz Foundation, an NGO dedicated to working on issues such as HIV/AIDS, as well as smaller LGBT groups, which came together, mobilising people for gay rights. The success of the movement does not, however, veil the fact that, since independence, India has continued to support and bolster Section 377.

Homophobic politicians

Two historians of gender and sexuality, Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai, in their book, Same-Sex Love in India: Readings from Literature (2000), called not just for the decriminalisation of homosexuals, but ‘full and complete acceptance, not tolerance and not sympathy’. Only that, they argued, would enable homosexuals to emerge from the shadows and lead a dignified life. For this to happen, it is imperative for India to acknowledge its social conservatism – the result of caste, class and religious discrimination, Western influence and a low rate of literacy – rather than simply blaming the colonial past for taking such a long time to repeal this law.

The sovereign Republic of India took nearly 70 years to guarantee a fundamental right to a huge percentage of its citizens. In 2015, India was one of 43 countries that voted – unsuccessfully – against equal benefits for same-sex partners working at the United Nations. Anjali Gopalan, director of the Naz Foundation, who filed the Public Interest Litigation against Section 377 in 2001, said: ‘This shows how homophobic the politicians in our country are.’ Across political parties, ministers and political leaders either dodged questions on gay rights or referred to homosexuality as unnatural and undesirable.

Victorious dissenters

The first sign of change was seen in July 2009, with a verdict delivered by the Delhi High Court, which decriminalised homosexuality among consenting adults. The decision, while extolled, also faced significant stricture. In 2012, the Supreme Court of India overturned the decision, saying that a ‘minuscule fraction of the country’s population constitute LGBT community’, and left it for Parliament to decide. In 2016, five petitions were filed in the Supreme Court, which argued that ‘rights to sexuality, sexual autonomy, choice of sexual partner, life, privacy, dignity and equality, along with the other fundamental rights … are violated by Section 377’. In August 2017, the Supreme Court declared that the right to privacy should be considered a fundamental right. Following this, the verdict of 6 September 2018 finally bore fruit.

The repeal of Section 377 can be attributed to the show of dissent by the Indian people. The popular sentiment in India, at least in the urban sphere, for the past two years was against 377, mainly because of the work of activists in garnering support across the country and across religions. From a handful of people in the first protest in the early 1990s, thousands took to the streets to celebrate the verdict in 2018. The repeal cannot, however, be seen as a long-awaited ‘casting off’ of the vestiges of colonial law and attitudes. The attitudes against which India’s LGBT activists have had to fight were perpetuated and entrenched at all levels of Indian society long after independence. To blame only colonialism is to absolve independent India of any responsibility for the treatment of its citizens. Now that the law gives them equality, will society follow suit?

Arnab Chakraborty is a PhD candidate at the University of York.